I recently attended an AI for architectural renderings workshop. The experience was both enlightening and overwhelming. Over the course of 10 hours, we dove into a highly technical process—a combination of multiple AI frameworks and tools to create wonderful architectural renders. The instructor, a talented architect / technologist, had figured out many of those workflows through experimentation and prepared fresh material that was impeccable and thoughtful.

I have massive respect for fearless warriors like him who dive head-first into figuring out complex workflows and generously share their experiments and learnings. These warriors push the industry forward, open minds and show everyone who is hungry to learn, what's possible.

Unfortunately, it was difficult for me to follow along, even as a battle-hardened technical nerd. My Mac couldn't handle the NVIDIA-optimized tools, and honestly, the maze of ComfyUI, Flux, Kontext, Kling, training with LoRa’s, Hanyuan and Rhino, along with multiple custom nodes to install, APIs to connect, payment plans to figure out, and a save-downloads-uploads etc.—all felt a bit too involved and reminded me, uncomfortably, of learning computational design all over again.

Surprisingly (or not?), some of what was being taught was already out of date—new foundational models and new developments had already superseded what was prepared only a week ago!

This experience highlighted a crucial point: while pioneers are pushing the boundaries of what's possible with AI in architecture, there's a need to make these tools simpler and more accessible for most architects who lack the time, desire or resources to master involving, complex workflows.

For the toolmakers, like us, I see our mission in not just enabling users to do their work better or different, leveraging the latest and greatest of emerging technologies, but making such tools accessible to 99% of the rest of the user—in this case architects, who don't have the luxury or patience to spend the time or money to wrestle with tech, and really just want to do design and architecture.

Visualization is critical to architecture. We are constantly asking clients or communities to imagine spaces from conceptual designs or floor plans and elevations. That's asking a lot—not everyone reads our architectural abstractions fluently. The human brain processes visuals exponentially faster than abstractions, and so architects started doing realistic renditions to bridge that gap. But traditionally, getting good renderings means time, hiring specialists or external consultants. This inevitably leads to additional dependencies, budgets, and bottlenecks. Besides, ‘outsourcing’ the process to a few experts breaks the flow of thought and conversations.

What if generating a photorealistic rendering was as easy as saving a view? What if exploring design variations cost nothing but a few clicks? What if visualization can join the conversation where it happens?

And so, here we are

At Motif, we decided to use the magic power of Google Gemini’s and OpenAI’s foundation models and introduce an AI rendering workflow in our tool. We optimized the process to understand buildings, and for how architects see and experience the world, giving visual responses that speak to architects' sensibility and aesthetics. The tool is incredibly easy to use, offering frictionless interaction as a single click to render, opening the doors to all architects, not just the amazing experts, to explore and express themselves generatively, during early proposal creations, or within collaboration/review environment.

In Motif, one can create great renderings with a single click and no prompt. Or go a bit deeper, selecting prepared render styles, modifiers, moods, and weather conditions in uncountable combinations. Or guide the software even further, with specific prompting, if one wants to guide the generation even more specifically.

I won't cover all the different render styles, preset modifiers, and environments that help you find thousands of variations and permutations for your visual style and explorations. Nor will I detail how you can bring to life a simple sketch, or a Styrofoam, balsa or 3D-printed model of your first concepts—the only way to truly understand this is to try it yourself. Instead, I'll share a few examples to illustrate that with Motif, you can make limitless visualizations and explorations and enhance your storytelling during design reviews in an enjoyable, effortless, and helpful way.

Lets do photorealistic!

If your goal is to generate a photorealistic rendering that brings your initial model to life, just place a ‘Motif saved view’ from Revit or Rhino, open the image generation toolbar, and go.

No expertise required. No prompts. One click—just do it.

You can of course, consider trying out some of the weather, environments or times of day or try out different materials for the façade.. The sky is the limit!

Beyond photorealism: the art of ambiguity!

When we architects begin tinkering with solutions, we know the path to a good building will belong—so we like to stay humble and non-committal with our early ideas.

Unlike Mozart, who believed each score was perfect, our initial designs are meant to signal the opposite. In early design, we avoid anything that feels final. Instead, we aim to convey to colleagues and clients: All doors are open. This can be torn apart and rethought.

Watercolor, B&W watercolor, and posterize offer that possibility. Something innocent, playful, that invites exploration, not a final deliverable

It all starts with a sketch

Every architect knows the magic of sketching—that mysterious force that moves your hand into doodles that gradually make sense. It’s our native language, a way to capture and express ideas more directly than words ever could.

As it happens, our AI rendering excels at translating rough sketches and early concepts into photorealistic or artistic visualizations—bringing the earliest ideas vividly to life.

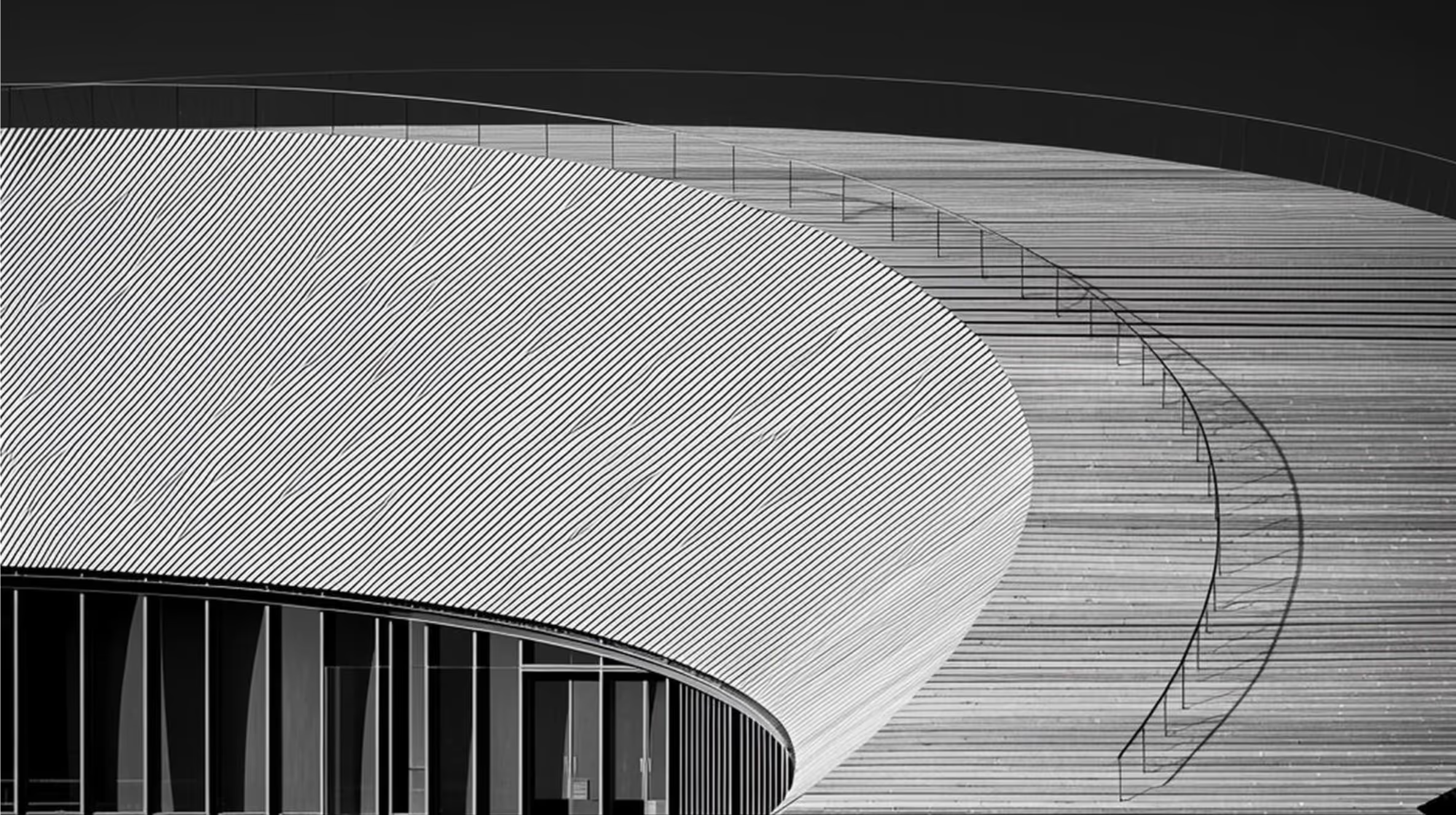

The timelessness of B&W photos

I wonder if anyone truly has an answer to why we architects are such suckers for good black-and-white photography. But for many of us, it’s pure bliss—for the eyes and the soul.

Whether it’s those flat, low-contrast B&W photos from the ’70 – ‘80’s, or Edward Weston’s high contrast, dramatic lighting and sculptural compositions, there’s something about B&W that reveals the deeper beauty of architectural form.

Louis Kahn profoundly understood the interplay of light and shadow in architecture—treating them as essential elements that shape space and stir emotion.

And nothing captures that interplay quite like black-and-white photography. Without the distraction of color, we focus fully on form, texture, light, and shadow.

Just look at this beauty we generated from a saved Revit view of the Viking Museum (Dorte Mandrup Architects):

To prompt, or not to prompt

Those who know me know I’m a language nut. I’m currently learning my ninth language and get the same thrill from clever expressions and crisp writing that others get from a slam dunk. (Ask my friends about the 25-cent penalty jar for using the filler word “like” in my house.)

All that to say: after three years of exploring AIs, I’ve learned this—language mastery pays off.

While we pride ourselves on offering a tool that doesn’t require prompt engineering expertise, there’s still something wonderful about using language to fine-tune and elevate your ideas.

The more creative, specific, and nuanced your words, the better the AI responds. After all, at their core, these systems were trained on language.

Where do we go from here?

Back in early 2021, while I was at IDEO, I was lucky to had a chance to experiment with some of the first image-generation models—well before they hit the broader market. We were asked: What would you do with such tools?

I chose to illustrate Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Ministry for the Future, which I had just finished reading. I no longer had the book in hand, so I recreated it from memory. The experience was intoxicating: my words and thoughts transforming into images at the speed of storytelling

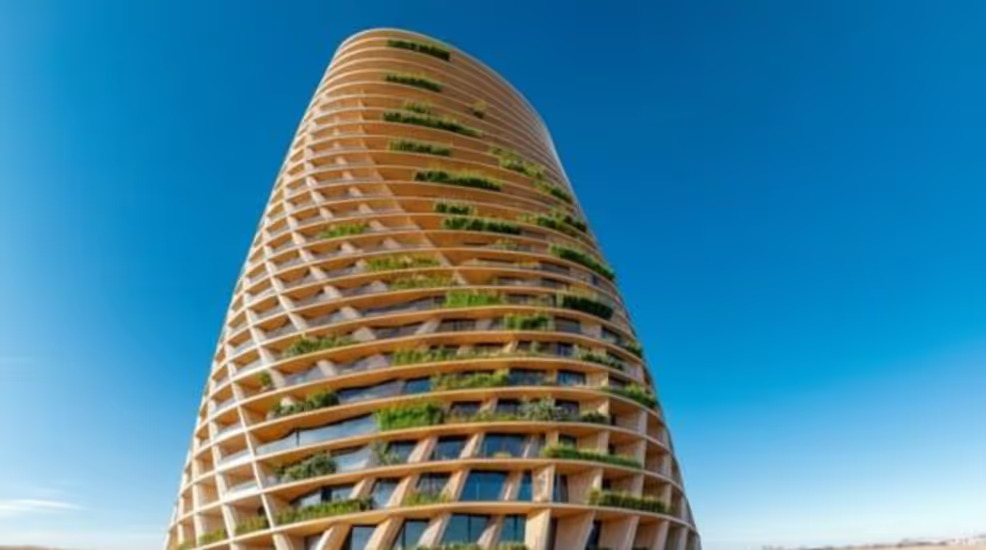

Then the floodgates opened—Midjourney, DALL·E, and countless others. Suddenly, the world was full of generative creations. And then I saw people using AI to make "architecture": Frankensteinian mashups of Zaha, Gehry, Gaudí or beautiful but unbuildable biophilic fantasies.

My first reaction was pure architectural snobbery: This isn’t how we architects work! This is a mockery of our profession! Is architecture just about formal expression? My whole being protested. And while I still believe there’s a line between meaningful exploration and aesthetic foolishness, I also see now that my Balkan, dramatic, passionate outburst was...well, wrong.

Architects fell in love with AI generation precisely because we are dreamers. We live in fantasy worlds but are asked to create real ones. We need inspiration, references, serendipity. We want to sketch an idea and see it come alive—to explore “what if” scenarios or depict possible realities at a finger snap and without committing to costly visualizations.

AI excels at this. It’s what I like to call “digital LSD”—only, better for your health.

What we offer at Motif today is a first step toward almost real-time, richer, and more playful visual communication—a seamless, intuitive dialogue between architect and machine. It’s our initial implementation of AI, interwoven into the design workflow.

So, where do we go from here?

We could talk about all the pragmatic improvements we’re planning to make this AI rendering even more powerful. But what’s more interesting is the bigger question: What does this actually mean?

Is it really just about quick generating of powerful renditions of early ideas? Or is there something deeper?

Can we imagine a time when these images communicate more than just a visual style or atmospheric fit? When they help us skip over premature deep dives into costly analysis—offering intelligent cues in the imagery itself? Could they help us move forward with more confidence in our design direction—based not only on emotional resonance but also on embedded, but some more meaningful insights and intelligence?

Methinks yes.

.png)